Measuring the Eye Gazes and Oral Language Skills of Preschool and Early Elementary Children

| Jacob Richardson, 4th year | |

| Madison Brodoski, 4th year |

Abstract:

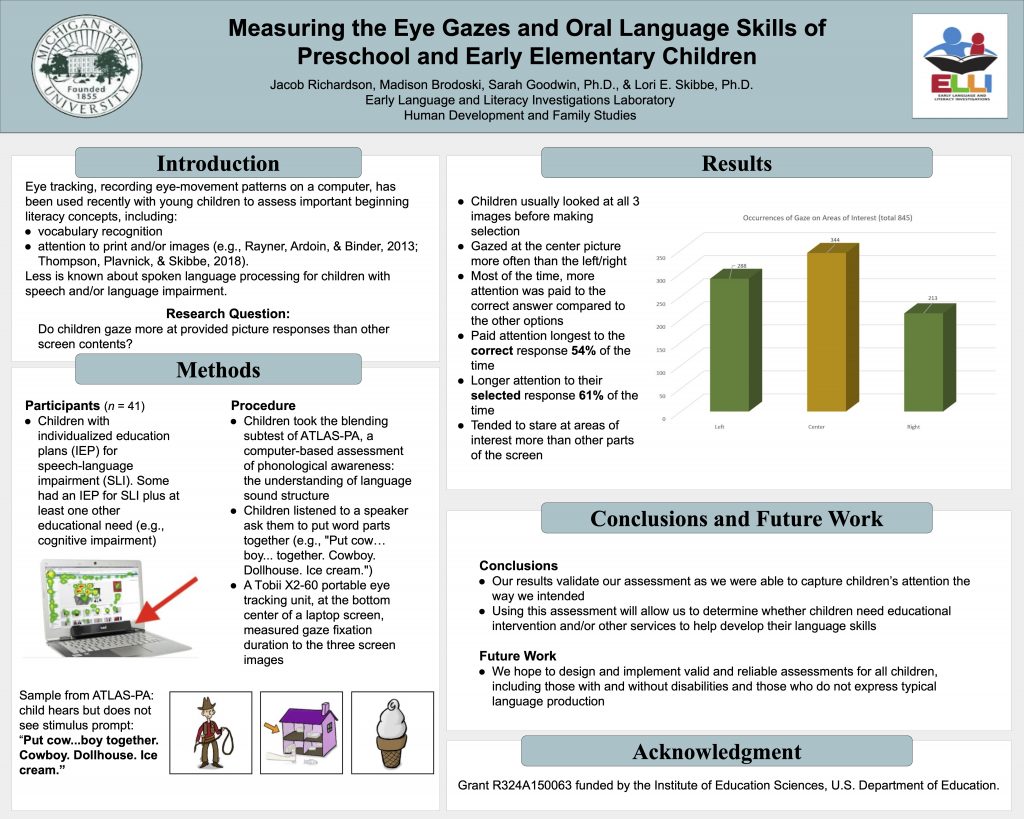

The present research uses eyetracking technology to examine how children with limited speech production attended to English phonological awareness (PA) items. Eye tracking, capturing eye-movement patterns with computer technology, has been used with young children, especially beginning readers (Rayner, 1986; Rayner, Ardoin, & Binder, 2013). With respect to early language and emergent literacy, eyetracking has revealed how children attend to recognizing receptive vocabulary items or picture book content (Thompson, Plavnick, & Skibbe, 2018). Determining whether children are focusing on core content impacts the design of early language assessments, especially for children who cannot verbally indicate their responses. Enhancing our understanding of children’s early language processing is critical to monitoring progress and determining appropriate interventions. Thus, this poster presents the eye gazes of preschoolers and early elementary children to investigate the attention they pay to computer-based test items designed to assess emergent literacy. Children (n=62; ages 3 to 8) with limited speech production (existing diagnoses including but not limited to autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and/or hearing difficulty) took a computer-based assessment of English phonological awareness (PA). PA, or the underlying sensitivity to the sound structure of language, is an important component of learning to read (McDowell, Lonigan, & Goldstein, 2007) and predicts later reading even after controlling for other early literacy abilities such as letter name knowledge (NELP, 2008). Recruitment occurred at 57 sites, including Head Start and Great Start Readiness programs and elementary schools. Participants represented diverse educational and socioeconomic backgrounds. PA items were presented on a plain white background one-by-one on a laptop computer, with tasks of rhyming, blending (e.g., “Put cow… boy together”), and segmentation (e.g., “What’s cowboy without boy?”). Stimulus words were all highly concrete and reviewed by experts with experience in special education and early language. Children hear the audio stimulus while being shown three images, where they or an assessor can mouse-click or tap on their chosen response. A Tobii X2-60 portable eye tracking unit was used to assess gaze fixation duration to the three pictures presented on each screen. The eyetracker data revealed that children with speech and/or language impairment tended to pay attention longest to the correct response. Moreover, children gazed at the answer options from left to right, similar to how typically-developing children behave (Skibbe, Thompson, & Plavnick, 2018). Children with speech-language needs looked at all three options on the screen, indicating that all distractors were functioning as intended. Although calibration of the eyetracker was difficult for children who were lower functioning on the autism spectrum or who had behaviors that severely limited testing, results suggest that we are able to use this PA assessment with most children who are not able to answer the expressive items often used in other PA tests. These findings indicate that young children, even those who do not use spoken language in typical ways, are in fact using the newly-designed PA assessment in the way we anticipated. Recommendations for future research and implications for practitioners will be provided.